Erik Raschke

Introduction

From 2001-2003, over three hundred refugees from all over the world moved to the small Arctic island of Berneria. In the spring of 2010, every human inhabitant vanished without a trace. In the fall of 2010, a U.N. freighter arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, with five cargo containers loaded with the Bernerians’ computers, diaries, and personal belongings. Since I had previously written about the colony, I was hired by the United Nations International High Commission for Refugees to sort through these containers and compile a cohesive narrative of their disappearance. An interactive app, to be launched in December, is designed to help friends and family of the Bernerians understand what might have happened to those they lost. Included below is an initial summary of my report.

Figure 1. October 17, 2010. U.N. containers from the island of Berneria.

History

1980

Beginning in 1980, the northern Arctic island of Berneria underwent what climatologists refer to as the Lippler Effect. The Lippler Effect, named after the New Zealand meteorologist Richard Lippler, occurs when certain greenhouse gases, upon colliding with the exosphere, create a kilometer-wide portal in which solar rays can be channeled, almost unimpeded, into our atmosphere. While the debate amongst scientists and politicians over the dangers of the Lippler Effect continues, the data shows that many of the islands in the far north of Russia have indeed become warmer.

In 1984, in the dead of night, an iceberg crashed through the hull of a Stanford research boat. The massive, multi-million dollar research vessel sunk in under an hour, in one of the most remote regions in the world – the Arctic Ocean

A week later, a small lifeboat from the Stanford research vessel washed up on a sandy beach. The sky was clear, the water pristine, the land dry, and the temperature as gentle as Southern California in spring. On this deserted island, two young graduate students, Richard Lippler and his sole surviving colleague, Lisa Knowles, built a home, gathered food, and lived comfortably. Almost two years later, a U.S. Navy submarine patrolling the area happened to see smoke coming from their chimney.

In the spring of 1987, Richard and Lisa Lippler, now married, returned to the remote island they called home. Arriving on a new research vessel paid for by the inventor of the Internet, Tim Berners-Lee, the couple began investigating why this single island, in the middle of the coldest part of the earth, was experiencing year-round temperatures comparable to those found on the equator. Their research led them to publish “The Lippler Effect,” one of the most explosive papers in the last century.

Figure 2. Berneria North-West Coast circa 1978, courtesy of ASWARC.

Figure 3. Berneria North-West Coast circa 1998, courtesy of Berneria Historical Society.

Figure 4. Richard Lippler and Lisa Knowles, courtesy of Stanford University Archives.

Figure 5. Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the Internet, after whom Berneria is named.

1990

Financed by Tim Berners-Lee and Berneria Real Estate Corporation, in the spring of 1989, Richard and Lisa Lippler, Les Vanderpool, and a team of seventy surveyors, biologists, ecologists, climatologists, and botanists began mapping the small Arctic island of Berneria. During this process, they discovered that crops such as wheat, sugar beets, rye, barley, and potatoes, -crops once attributable to more northern latitudes such as Canada and Finland- could now be grown on Berneria. After rigorous research and measurements, they concluded that the crops in Berneria grew 5 to 9 times faster than their counterparts in more southerly climes.

In the southwest portion of the island, Druidic markers were discovered. The Berneria Historical Society quickly procured funding from the Royal Academy of Archeology for further study (see cover photo).

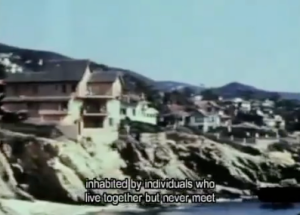

Very early on, Tim Berners-Lee and the Lipplers began drafting an egalitarian charter for what they hoped would be a new colony, inhabited by individuals from all around the world. In an International Herald Tribune interview with Tim Berners-Lee, he said that his goal with Berneria was similar to what he did with the World Wide Web, which was to take disparate, existing concepts and “generalize” them, i.e., using the brains and ingenuity already present in humankind to create the “greatest” colony in the world.

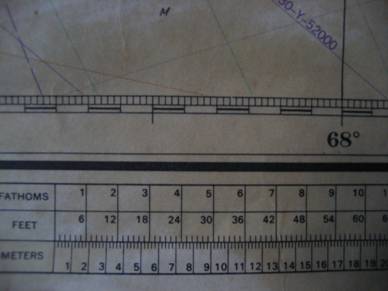

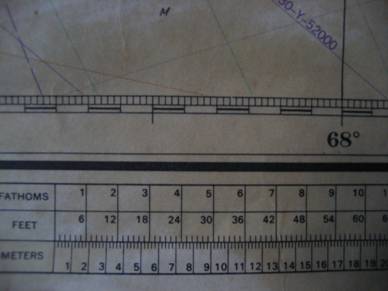

Figure 6. Earliest survey of Berneria Harbor, courtesy of Berneria Historical Society.

2000

In June of 2003, Les Vanderpool of Berneria Realty Corporation contacted me to write a series of articles about the new colony of Berneria. After three heavy days of travel, I spent June 2003 to October 2003 walking the island and visiting with Bernerians. To say the least, it was a revelatory experience. I was among hundreds of people, from every part of the world, beginning a new life. We were over a thousand miles away from any major metropolis, hundreds from any commercial outlets, and yet, among these Bernerians, there was nothing but hope, confidence, an unstoppable drive to redefine humanity’s potential.

However, in May of 2010, after repeated and unsuccessful attempts to get in touch with Les Vanderpool and arrange another visit, I went to Berneria on my own accord. Without the help of the various drivers and pilots working for Berneria Real Estate, it took me almost 10 days to get to the island. When I arrived early on the morning of June 5, 2010, I found the colony deserted. I discovered doors unlocked, meals half-eaten, dishes unwashed. However there seemed no sign of struggle, and no significant damage other than erosion. The Bernerians were simply gone.

I combed the island and during my ten weeks there could find no single answer to what happened except the name “Melville” scratched upon a tree in the town’s square. Melville Island is about a 10-hour trip northeast by boat from Berneria and since I was funding this trip out of my own pocket, I could not afford to make the exploration.

Figure 7. Les Vanderpool, Director of Berneria Real Estate.

Figure 8. Computer generated collage of the 300 inhabitants of Berneria which hangs on the wall of the now abandoned Berneria Real Estate offices.

2010 – Present

With the cargo containers safely stored near my home, I have begun to slowly unravel the mystery of the disappearance of the Bernerians. Every few weeks I will be updating the Berneria app with my findings. In the meantime, I have concluded that the per capita number of suicides reached levels unseen in any previously documented colony. I am convinced that this was not due to the remoteness of the island like some U.N. representatives have publicly claimed, but because of the objects and possessions which regularly washed upon shore. These “items,” many stored at the Berneria Historical Society, were physical manifestations of some deeper collective anxiety. Toward the end of the last year, these Bernerians, many of them highly-educated, secular individuals, started a church in which much of the ceremony involved “self-renunciation.” Much of the liturgical text refers to Kant and Kierkegaard as well as the writings of the highly-acclaimed poet Ho Jing, who fled China in 2005 and became a Bernerian citizen in 2006. I have sent copies of Ho Jing’s prophecies to several Religious Studies academics in Europe and America for further analyses.

Sample Journal Entries:

Nienke, June 30, 2001

I am sure it will take us most of the summer to recover from the loss of Francine Fromme. Everyone has been concealing their impatience or irritation under thin, painfully somber smiles. We nod and say hello, but conversation never seems to go much farther. Francine’s suicide has turned everyone into turtles, retreating without hesitation into themselves.

I refuse to walk along the beaches for fear of what I’ll find. Two weeks ago, on the upper north beach, Armen Mankarian, from Charents-Sevan, Armenia, found the hand coffee grinder that his father used to beat him and his mother with. Yesterday, I saw Sarah Bishop at Dr. Imjay’s office begging for Valium. She had just found the beaded steering wheel from her junked Toyota Camry lodged between two rocks along the southeastern cliffs. She said that the wheel still had blood on it, blood from the man she hit six years ago on The Cleveland Memorial Shoreway.

The only people who seem to enjoy the clutter lining our beach are the children who find endless new sources of entertainment. This morning I went to Enka’s restaurant and saw Oladele Nwokolo, a Nigerian boy of about seven playing with a rubber shark. He and his mother, Gimbya, had just been for a walk along the harbor. I am pretty sure the shark is the same as my son’s. When Sander took baths, in his little plastic tub, his skin slick from scented oil, he played only with that shark, circling it between his little legs, submerging it into the bottomless depths to hunt for imaginary prey.

Figure 9. Nienke

Sarah, July 3, 2001

O.K. So here’s the third law I’m proposing. It’s called the “Get Over Yourself” law. If someone gets way too hung up over something lame, then they get imprisoned until they can prove that they’ve chilled out. It doesn’t matter what it is. It could be shoes or abortion. Think about how rational conversations would be. Everyone would be worried about going to jail so they’d totally start listening to each other. How do you define “lame…” you might ask? Well, “lame” would be like “the right to bear arms” in the American Constitution, and Berneria would have judges like me interpreting the definition. “Lame” could mean “teachers who don’t let students text in school,” and then in ten years it could be like “old people driving rockets really slowly.”

When I finished drafting my law, Altunai came over and we made a bunch of hot cocoa and cider, put it in cups with lids, and went down to the harbor. In less than ten minutes, our tray was empty and we had to go back home and get more. We made fifty Berners between us for like an hour’s work. I told Altunai that we probably could have sold even more, but then those Muslim guys came and everyone got distracted. That evening, I showed the cash to my mom and told her I planned on using it to hire some movers to bring the glass table back from the beach. She told me I had manipulated a tense, unpleasant situation at the harbor for my own self-profit.

So? Isn’t it a free market?

Anyhow, Altunai and I gave three cups free to the Guantanamo prisoners as they passed by my house. It was so gross because they got whip cream and cocoa foam all caught up in their weird beards. Yuck. I think it was only because Altunai said “assalamu alaikum” that they drank it at all.

Welcome to Berneria fellas!

Not.

Figure 10. Sarah

Erik, June 30, 2003

Land

At three in the a.m., peering over his gas lantern, his rheumy eyes like freshly shucked oysters at midnight, the deckhand shook me awake. I dressed, and made my way to the stern, where I gazed into the freezing darkness. It was not until I made out the shadowy outline of land and we were a few hundred meters from shore that I saw the dim light of the harbormaster’s office. How disappointing after so many miles of travel to discover only a sleepy hamlet with little more than a desk lamp serving as a light tower.

The harbor was littered with ice, no doubt the remnants of the many ghostly icebergs that we passed on our way here. The captain cut the motor and our vessel pressed through the frozen debris as we glided toward land. Two African boys, accompanied by an older woman whom I judged to be their mother, fastened our ropes to the dock and laid a plank for us to cross. Oddly enough, once the boat was steady, I found myself crossing alone. The captain who had delivered me here so safely had no intention of going ashore.

The air here was surprisingly warm yet dry, like an August alpine afternoon. From what I could tell in the moonlight, the beach was composed of what seemed like large, rounded multi-colored pebbles, most likely smoothed by the hundreds of feet of ice which once covered this land. There were groves of saplings on the eroded cliffs, but most of the landscape appeared to comprise grass and shrubbery; but, like I said, it was hard to be certain in the dark.

Once I was safely on land, the deckhand grunted to the African boy and then the boat was unfastened. With a loud grumbling, the ships engines groaned into reverse. The deckhand, still busy coiling the rope, faded into the night without a wave goodbye. The captain switched off the light in the steering house, and the ocean became an uneven pattern of darker and darker movement.

Inside the tiny harbormaster’s office, which was not much more than a log hut, I was offered coffee and introduced to Mbali Van Gertz and her two sons, Manelesi and Ulwazi. I told her my name and where I was arriving from. Her two sons stared at me; the youngest of the boys, I realized after a few quick glances, had a glass eye. The other had a scar that traveled the length of his cheek and neck.

Mbali labored over each letter of my name. I occasionally smiled at the boys and asked them how they liked it here. Their replies were no different than the casual declarations of American youth: half-shrugs and sucked teeth. Ulwazi nodded toward Manelesi’s skateboard in the corner and boasted that they were building a half-pipe near the end of the harbor. Stupidly, I asked what the half-pipe would be used for and was once again directed back toward the skateboard. Seeing that I obviously had little street cred, the two boys left, explaining that Les Vanderpool had requested to be notified immediately of my arrival.

When the boys were gone, I asked Mbali if she was from KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. She nodded and said that her father had been an Afrikaner from Johannesburg, although she only saw him two or three times. He had several children spread out over the province.

“Have you been to South Africa?” she asked.

“Yes. For a week.”

“Did you like it?”

“It was like nothing I’ve ever seen.”

She nodded as if this were an acceptable answer and said finally, “You are the first American I have met who has been to my country.”

I was tempted to ask Mbali how she had come to Berneria, or better, how someone barely literate, and from such a disconsolate province, could have afforded the long journey. I asked Mbali if I could interview her in the weeks to come. She said, cheeks high, more wincing than smiling, that she would have to consider it.

I filled in a few forms and studied the temporary Bernerian Charter hanging from the wall. Within fifteen minutes of the boys’ departure, Les Vanderpool arrived at the office. He was a cheerful little man who excitedly shook my hand, although I suspect he would have preferred a hug. He still had the same mullet hair cut (which I had seen from pictures when I Googled his name) and a loose-fitting button down flannel shirt. He was neat in every way with his jeans rolled to the top of his sensible hiking boots, his face cleanly shaved except for a tightly trimmed mustache, and his hands and nails delicate, almost feminine. Overall he appeared as a divorcee and who suddenly, for whatever reason, had been thrust into the general instability of single-life and thus had turned to the predictable regiments of ironing, cuffing, creasing, and coiffing.

“Did ya get seasick?” he asked in a slightly mocking tone. “Some of the stories we’ve heard, right Mbali? One little girl threw up sixteen times. The mother was sick seven or eight times. The father too! That old deckhand had his work cut out for him, eh? But they’re happy now. That family. Put the whole experience behind them in just a few days.”

He then glanced over the forms that Mbali had just completed.

“We can get anything we missed tomorrow. I bet Erik’s tired. Need to be rested for our hike tomorrow.”

Les spoke a few words of isiZulu to Mbali who only nodded back. Then, quite condescendingly, he patted Ulwazi and Manelesi on the head, and we bid our goodbyes. Mbali appeared neither excited nor disappointed by our departure, and was in fact as emotionless as a bureaucrat late on a Friday afternoon. I, however, was glad to be moving, glad to be heading toward a comfortable bed.

Les took my suitcase, rolling the wheels along the bumpy gravel road. He chatted about the weather over the last few days and how the Lippler Effect had given Berneria a gentle climate, but how it had also robbed them of long afternoons, as when he had lived in Seattle and Maine, locked in the house reading a book while the rain battered the windows. When there was inclement weather in Berneria, he moaned, it occurred only in the evening, after one fell asleep.

While we walked in the dim, pre-dawn light, I could make out a land that was rather barren, with Alpine grasses and bald patches of granite. I noticed pine seedlings stretching over a hillside, budding in rows, planted by the Bernerians for use as future timber. Some patches of trees had even grown to a reasonable height.

Somewhere along our walk, Les began to tell me about a program he heard on National Public Radio, via the Internet, about Republicans taking money directly from insurance companies and then looking the other way when hospitals tossed the poorest of the sick out onto the streets. The hyperbolic wrangling and hostile concern over federal policymaking, whether authentic or not, still had the ability to make his blood boil. For Les, the NPR story had relit the dark frustration of injustice with such force that the tremendous silence of Berneria at dawn was unable to ease his agitation.

“Here’s something,” he said, “that happened here and perhaps you shouldn’t repeat it because, well, as a journalist it is hearsay really, but a few months ago a family from Sudan arrived on our beaches. They were ill-equipped for the weather, had not a cent to their name. They went from house to house and each and every Bernerian gave them something. Coats, socks, food, you name it. All except one man. His name was Bertrand Beachman from Devon, England. Said that he moved here to ‘get away from the lazy.’ He was very vocal about his unwillingness to help anyone in need. He quickly adopted the nickname, Bertrand the Nazi.” Les paused here and chewed on the edge of his moustache and then continued:

“Two months ago his house caught on fire. He came running into the empty street for help. Begged. Pleaded.” Les cut the air with his index finger. “No one came.”

“Jesus.”

“The next day the family from Sudan brought Bertrand Beachman a thermos of coffee and hot oatmeal. We all felt ashamed. Our pettiness burned. They talked. Bertrand explained himself. The Sudanese father understood. Said that he didn’t like ‘lazy’ people either. Unfortunately, Bertrand took to wandering the streets and the hills. Something about that fire had snapped the life in his soul. A week after his house burned down we found his body washed up on the shore. He had jumped from the cliffs.”

Les looked me in the eyes. Then he looked away and kicked a stone. “The history of colonies and communes has been more negative than positive. One collapse after another. I’ve done my reading. I know it’ll take a lot to make Berneria work, but this island is much more than an experiment. Too many people can’t ever go back. It’s either prosper or perish for them.”

We walked the rest of the way in silence. There were no birds, no crickets, no sounds whatsoever. I could hear, however, the sound of Les’s labored breathing as he insisted on rolling my heavy suitcase.

Figure 11. Erik

Additional information

For the Google map of Berneria, click here, for Berneria Real Estate, click here, for Berneria Historical Society, click here. The app will be available in December 2012.

_________________________________________________________________

Erik Raschke grew up in Denver, Colorado and received a Masters in Creative Writing from The City College of New York. He taught in Washington Heights, Manhattan, for many years. His first novel, The Book of Samuel, was published by St. Martin’s Press in the fall of 2009. He lives with his family in Amsterdam where he is currently finishing up his second novel, Action at a Distance.